How Project Managers Run Projects: A Beginner’s Guide

What is the matter of this post? The main reason why I chose this topic is to help beginners test their awareness and start building a bridge between theory and practice, and perhaps get rid of stereotypes. The material is primarily aimed at juniors and trainees in PM, but it can be useful for other IT specialists. And of course, I want to bust a myth that a parrot can be promoted to PM if he can say "well, what's there?".

What is a project?

The classic definition is that a project is a temporary undertaking to create a unique product or result.

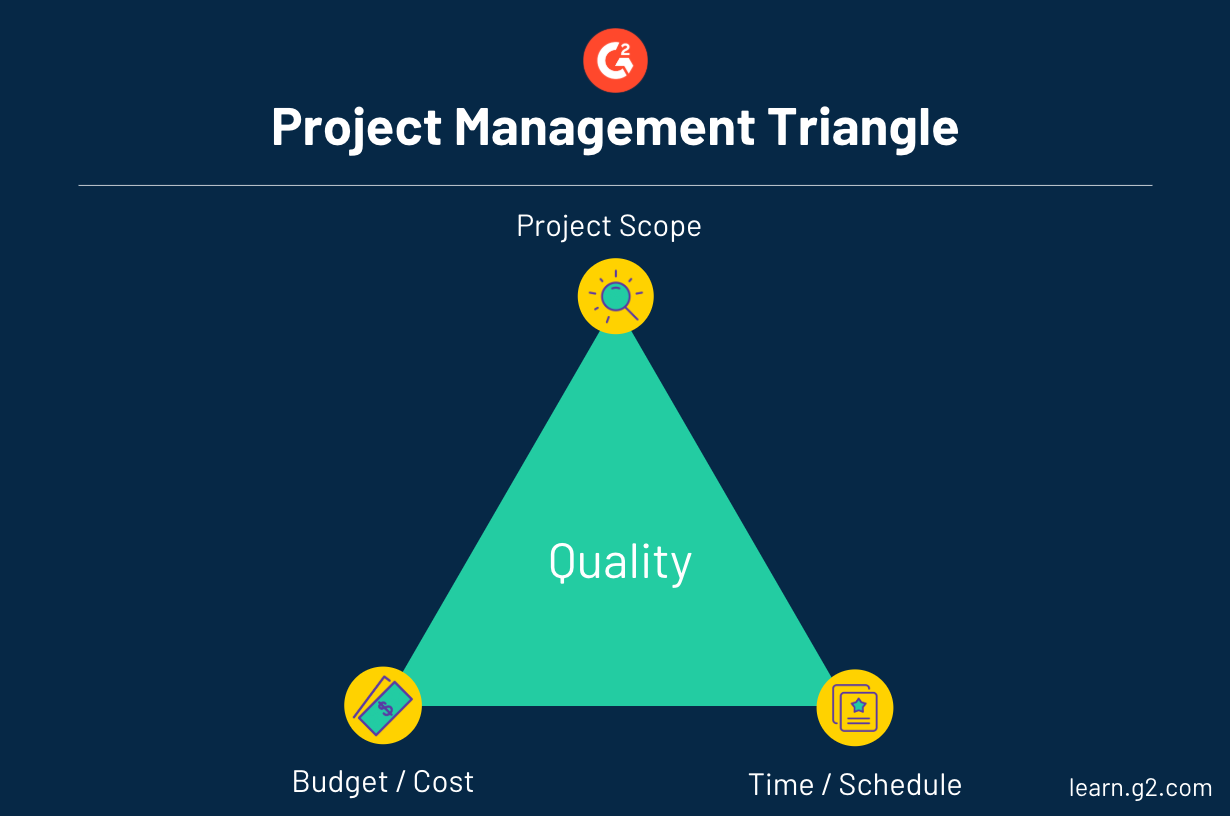

But for a project manager, this is not enough: you must always take into account the scope of the project, the cost, and the time of work. These elements are called triple boundedness.

The essence of the triangle is that you cannot select everything at once - you need to try to maintain a balance between the elements. Depending on the tasks and processes of the project, you can choose two constraints, while sacrificing the third. Many, cheap and fast will not work, although this is the principled position of many customers.

Project definition for real PM

An event to create a product or result within a specific timeframe, budget, and with the proper quality and/or defined scope.

Manager's Star Map

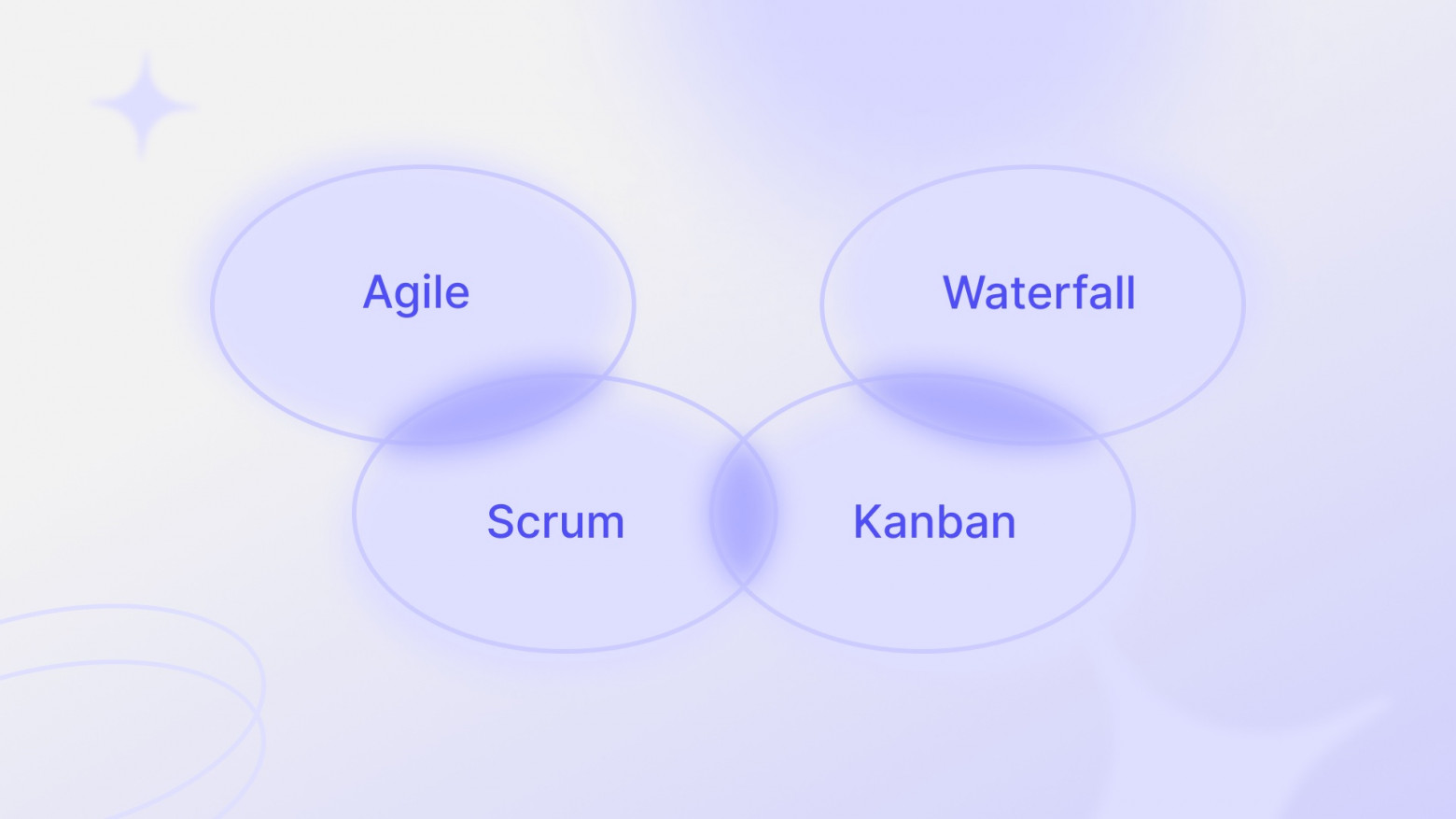

Agile - is a philosophy (value system, flexible way of thinking, mindset) that helps developers make new products faster and better from a business point of view.

Scrum - is a set of tools, a framework with which the Agile approach is implemented. In Scrum work is done in sprints - iterations of the same duration.

Kanban - is a development management and process visualization method. Determines exactly what needs to be produced, when and how much. Historically, kanban is just a board, now it is made into a separate framework - a kanban method.

Waterfall - is a conditionally existing waterfall development model. Here, the process is perceived as a flow, and the transition from one stage to another occurs only after the successful completion of the previous one.

These concepts intersect and interact with each other in the following way:

Which approach to choose?

Globally, there are 2 development models: waterfall and iterative.

The cascade development model involves the sequential passage of stages: requirements, analysis, design, implementation, testing, integration, and support. The transition from one phase to another is impossible without the complete completion of the previous one.

It is opposed to the iterative model when the creation of the product is carried out in parallel with the continuous analysis of the results and the adjustment of the previous stages of work. Most often, such a model is chosen when the total amount of work cannot be determined at the first stages.

For example, let's take a look at two projects. The first one had a clear release date, a clear scope, and a limited budget. Second - an indefinite release date, a backlog of tasks for a year, and an unfixed budget, which is calculated by the number of hours spent by the development team per month.

Of course, these projects should use different development models.

At the moment, the iterative model and Agile, in general, are the best they have come up with in terms of delivering value (quality and speed) to users. Let's focus on these concepts. It's worth mentioning right away that Agile flexibility is not getting rid of the framework and everything that was too lazy to do with the standard approach. Many perceive it this way, but this is a sure way to failure.

Agile ≠ Laziness ≠ Silver bullet

Like any philosophy, Agile needs to be comprehended. As in any philosophy, its principles are exaggregation, and exposure in order to make it clearer. This is not a framework, and therefore it must be used consciously.

Let’s start our journey with 4 main Agile principles

There will be a lot of text because we need examples to better understand Agile principles. Because even someone’s experience with low efficiency is better than a clear theory.

1. People and interactions are more important than processes and tools

The bias in processes is too formal and kills horizontal communications, which means it reduces the speed of value delivery. In such companies, memos are written and you need to put in 10 signatures before agreeing to the main one. The speed of feature delivery can drop sometimes to zero.

Imagine we started developing a mobile application for a large flight company. At the beginning of the cooperation, you understand that getting API access worked only on assignments. And in the assignment, you must specify the API calls you need access to. It turns into complicated communication between teams, and the processes took longer than you can expect. What can I do if they are bureaucrats? Good question. You can set up direct communication channels with responsible persons, introduce to them weekly scrum of scrums, and then achieve the desired synergy. Will these actions reduce time to desired one? Probably not, but believe me - it will be faster than without taking them.

But what happens if you completely hit the first part of principle - people and interaction, ignoring the second - processes and tools? People will solve all issues uncontrollably and chaotically. Constant interaction will reduce efficiency and leave the feeling that you have not done anything useful. It will quickly become clear that, in addition to interaction, you also need to work.

For example, at some point, we encountered a situation where developers began to complain about frequent distractions because there was not enough time to calmly think about the code. We listened and gradually introduced “hours of silence”. This is the time when developers can safely work without fear of being pulled out of their process.

2. A working product is more important than comprehensive documentation

Let’s think about what happens if we don’t give a damn about the documentation? We will get a quick profit and a big risk, which is commonly called the bus factor.

Imagine that in your full-agile project, the one and only backend developer (”you don’t need more. because sometimes he has to test anyway”) is crippled by illness. He, of course, will return to the project, but only in a month, when he finally recovers. I think it is not necessary to explain what will happen to the project.

If we start running into frequent product demonstrations, then we risk falling out of the critical path - the order in which tasks are performed. The Agile principle says “let’s get the product faster” and the Scrum framework implements it as “let’s make frequent demos”. But this can seriously affect the way developers work, especially on large projects. Sometimes, in terms of timing, it will be more profitable to build a critical path so that it is more convenient to develop rather than show.

And what will happen if you don’t give a step without specs and requirements? The probability of the release of the project on time will be extremely small. Most likely, you will drown in agreements.

The output might be:

- start development on part of the requirements;

- retrospectively update the requirements if they have changed during development.

3. Cooperation with the customer is more important than agreeing on the terms of the contract

Close cooperation with the customer is necessary in order to form a trusting relationship with him and his involvement in the project. The more the customer participates in the process, the more he considers the result to be his own too. At the same time, the product development process becomes more transparent and the risk that the project will not be accepted is reduced. Do you feel the difference between seeing the result in six months or being aware of the development of the project every 2 weeks?

In custom development, these two concepts - cooperation and agreement of conditions - are not antagonists. Rather, they are two parallel streams. It is in the interests of the company to keep track of both: if you don’t get a contract, you won’t get money.

I had a case when we were very carried away by involving the customer in the project and did not have time to agree on a new scope of work. This led to the fact that some of our amount of work remained unpaid. This is because with large customers, the workflow takes a decent amount of time, and on government projects in general it may require a separate manager and team. Lessons learned. Thanks to this story, we decided to transfer the process of negotiating the terms of the contract to account managers. So when the project manager or business analyst sees that scope may grow, he reached the account manager - and the negotiation workflow with the customer begins.

4. Readiness for change is more important than following the original plan

In my opinion, this is the most difficult point, because it involves psychology.

Strictly following the plan, you risk releasing something that will not be needed. People who create a product feel uncomfortable when they have to work at a desk, delay release or quit halfway through. No one likes to do unnecessary work or throw away their result. Working in CRM and task manager implementation and development, I even met tears when a banal change request for something that was obvious for the specific customer required rewriting the whole module of the product.

Not having any plan at all is even worse. There is a risk of playing with improvements and not releasing the project, getting stuck at the "let's finish this one more" stage. This ailment I call "release impotence". It affects many PMs, products and customers.

But there is also a downside to being flexible

If we stick to flexibility at every stage of development, it will grow exponentially. Flexibility will multiply!

Let's what can happen in an example case:

- The analyst wrote requirements for the entire feature scope at once, including cases outside the agreed scope.

- The designer drew the flow the way it will be after 15 releases.

- The backend developer made one method out of the required 4. Moreover, in the course of development, he changed the nesting and types of variables, because it is "more correct" this way.

- The developer was told on the fingers what needs to be done now, and what can wait until the 15th release. He completed the task, along the way verbally agreeing with the designer about the elements that he forgot to draw.

- And now let's imagine that this has reached QA:

- full requirements, taking into account nuclear war and the invasion of cockroaches;

- flight of the designer's fantasy for 15 releases ahead;

- the harsh reality in the form of an application that only in general terms resembles the requirements and design.

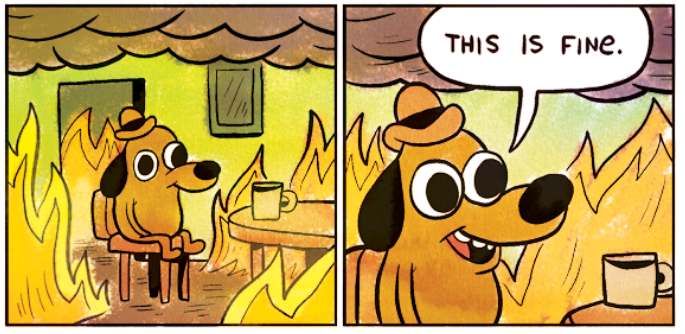

The rest of your communication skills will spend on putting out local burns of a QA engineer and explaining what exactly needs to be tested. 5 sprints in this mode - and you can be taken out.

And what to do?

You should keep a reasonable balance and look for a middle ground.

Each project requires an individual approach. What worked on one may not work on another. In order to manage projects well, PM looks for the golden mean in every Agile principle, starting from a specific case.